Simplify Components by Separating Logic from Presentation using Adapters

It's tough to know when it's the right time to break a component up into smaller components. Here's a way to approach that process that relies on more than what you see on the screen.

Components are a total game changer ... if you know how to make the most of them. Otherwise, they can become overly complex and unwieldy, and you may wonder what all the fuss was about in the first place.

Often what drives that complexity has a lot to do with when you decide to break the component into smaller components. Do it too early and you have way too many components and all this unnecessary property drilling, which leads to a nightmarish maze when trying to find where some element lives in the codebase. On the other hand, if you do it too late you'll end up with massive, overly-complex components that are intimidating (and often risky) to refactor.

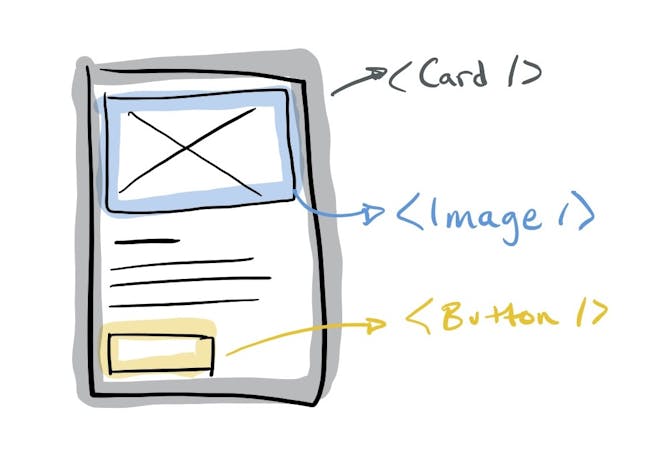

Many times when we think of simplifying a component, we think of breaking it up into smaller structural pieces, or subcomponents. For example, a card component may have an image, some text, and a button. It's a simple and static component, and it may make sense to pull out the image and button as separate components (i.e. subcomponents).

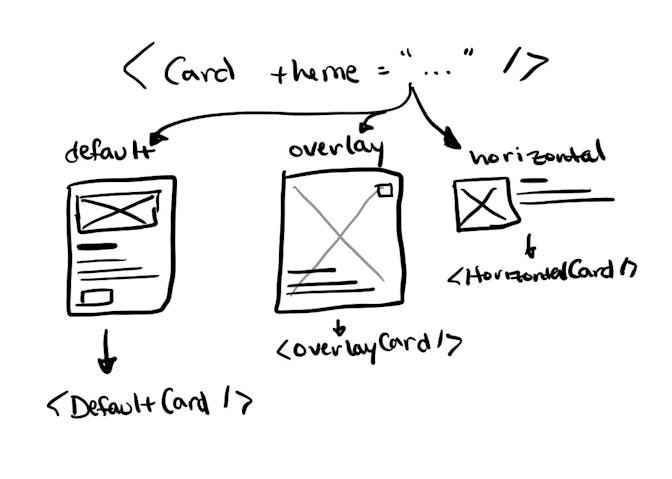

Or maybe your card has multiple theme properties that determine the other properties it can accept and how it is rendered on screen. In this case, it might make sense to simplify the various themes by building a component for each one and having one controlling component accept a theme property and determine which card component to render.

In both cases above, my assumption was that those components were fairly static. They accepted a series of properties and used the values to render something statically on the page. In other words, breaking them up — whether into variations or subcomponents — was entirely structural, or based on what we see on screen.

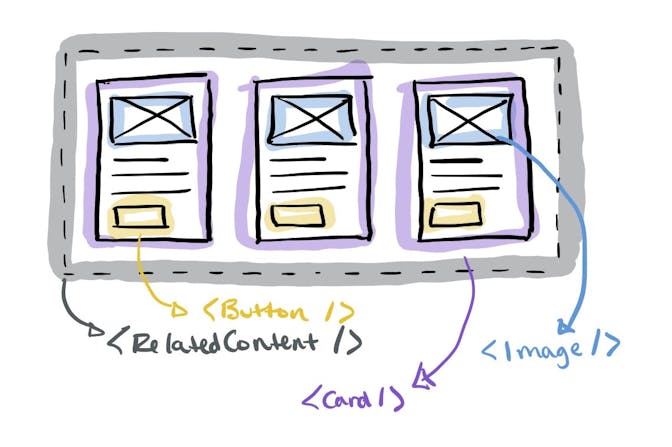

Now, consider a related content component. It's more dynamic. It accepts the current piece of content, then looks at the data source to pull three pieces of related content, and displays them in a grid of cards on the page.

That's a lot going on in one component. When it comes to breaking it up into smaller components, it's likely that the first effort is going to be structural — you'd pull out the repeated card as its own component. That makes sense — it's what I would do, too.

But then we're left with this related content component that has multiple responsibilities. It has to go fetch data, transform it (maybe), and then render the content to the screen, which also means controlling the styling.

Breaking up a Component Functionally

What if, instead of breaking up the component structurally — based on what we see on screen — we broke it up functionally? What if we separated logic from presentation?

In other words, in this example, I could see us having four levels of components:

- The related content component is responsible for fetching and transforming the data. It then renders ...

- A card grid component, which accepts data for an array of cards and controls the styling of the grid. It renders its contents by passing the properties it received into ...

- Several card components, which use shared subcomponents, such as ...

- An image or button component, which are statically rendered to the page.

Introducing Component Adapters

I call logical components — like the related content component — adapters. They don't bring any styling. Instead they wrap a component that is responsible for the styling. The adapter stays focused on retrieving and normalizing data so that its subcomponents can focus only on styling.

This approach separates logic from presentation. It means that the components responsible for styling don't have to know anything about the data source. So if the data source isn't ready or available, we can still see the same result on screen, simply by passing static (or mocked) data to the top-level presentation component (card grid/), bypassing the logical wrapper (related content/).

Benefits of Component Adapters

I've found three primary benefits to this approach.

First, it adheres to the single-responsibility principle, in which every component does one thing and does that thing well. At first we were asking a single component to play a logical role (fetching and transforming data/) and a presentation role (styling cards on the screen/). To pull it apart means we've simplified our approach by letting each component focus on doing one thing well.

Second, it's easier to test. The adapter would be tested for ensuring that it can properly transform data and that it leads to some content on the screen. But the card grid (and subsequent components) can be tested visually in isolation, without the need for a data source.

And last, the ability to test in isolation leads to an ability to develop in isolation. I've found this to be extremely beneficial to the development process. It helps UX/UI developers stay focused. They don't care about the dynamic data, they just want to make sure it looks good when it's there. This may also help avoid conflicts as back-end and front-end developers would rarely be working in the same files.

Potential Downfalls of Adapters

This approach doesn't come without its tradeoffs. It arguably still increase the complexity of the application by decreasing the complexity of the components. Breaking out adapters means a higher number of files in the project, which could lead to a difficult time for a new dev jumping into a project fresh. But that's why I clamor for consistency across projects — so new devs learn your approach one time and then they are comfortable in whatever codebase they get thrown into.

I also don't have an in-depth test on the effect this approach has on performance. With the projects I'm typically working on, most components don't have adapters. I may have somewhere between 3-10 adapters on any given project. If I were using this approach on every component on a large project, I would feel more compelled to study the effect on bundle size and performance.

Environmental Context

One last note I'll add before I wrap is that this can get hairy when a component farther down in the tree uses an adapter, but you don't always want to use that adapter.

For example, perhaps early on in a project's life I want to not include any adapters, but instead use static data, because my data source isn't ready to use yet. Yet, I still want to be able to start building adapters.

In that case I've used another type of adapter that looks at the environment and then renders the appropriate component.

That's all I have for you on this topic today. I hope this got your brain gears turning. This has been on my mind much lately. I always welcome dissection and criticism of topics like this, as it makes my work (and yours) stronger. Or if you have questions or want clarification, bug me on Twitter to get a conversation started.