Component-Based JavaScript Architecture

Keep your JavaScript code organized by continuously abstracting it while focusing on patterns within your site's components.

It's really easy for JavaScript to get out of hand. We've all been there. The classic case is when a project loads a single JS file wrapped around a $(document).ready() callback. All the functions and functional JS are strung together in this file in a way that is unclear to anyone else who many dare to enter.

It's easy to make the excuse: When it works, it works. But that only really works for the original developer for as long as they remember what the heck is going on within that file. Add another developer or a little time and all of a sudden it's a bear to move through that file and squash a bug.

It's not a good design for the longevity of any project. And it's especially not good when there are multiple developers collaborating on a project. Ultimately the decisions we make with the architecture of a project's JavaScript code can become expensive over time.

An Example

Let's take a fairly common scenario and look at how we can abstract messy JS code into clean, abstracted components.

Consider a case where there are two elements within a site that do essentially the same thing within different contexts. Let's say there is a button that triggers the showing and hiding of the main navigation menu, and there is also have a button that triggers a modal window.

The HTML may look something like this:

<a href="#" class="menu-trigger">Menu</a>

<div class="menu">

<!-- Menu Content -->

</div>

<!-- ... -->

<a href="#" class="modal-trigger">Modal</a>

<div class="modal">

<!-- Modal Content -->

</div>And let's say all the site's JS code is in a single file, which looks something like this:

$(document).ready(function () {

var modal = $(".modal"),

menu = $(".menu");

$(".modal-trigger").click(function (event) {

event.preventDefault();

modal.toggle();

});

// Do lots of other stuff ...

$(".menu-trigger").click(function (event) {

event.preventDefault();

menu.toggle();

});

});The Issues

There are (at least) six issues with this approach:

It's not DRY. These are two simple functions and they both are performing two simple tasks -- prevent the browser from doing the default with the link/button and then toggling the visibility of some element.

The targets are assumed. In both cases the JS is assuming it knows how to target the affected element (e.g. the

.modal-triggerwill always affect.modalelements).Variable scope is shared. The modal event handler has access to the

menuvariable and the menu function has access to themodalvariable. The are both unnecessary circumstances without any added benefit.Distance between

menudeclaration and use could be large. Whilemodalis defined right above where it is used, if the code represented by the comment gets long we could be left with a vast distance between instantiatingmenuand using it. When inside the menu callback and looking at themenuvariable, it's unclear what it is and where it was defined.JavaScript is determining visibility. This is something I always used to do. It's really tempting to use the

show(),hide(), andtoggle()jQuery functions. But it's not a great practice. It's best for any given project if we let CSS handle the styling of elements and let JavaScript focus on the functionality of those elements.Classes are determining functionality. On a similar note, I'm using classes (

.modal-trigger,.menu-trigger) to determine the functionality of these elements. Classes are for CSS to use for styling. We have other ways to target these functional elements. Just because I can target classes with JS doesn't mean I should.

Cleaning It Up

Let's address each of these six issues with one new solution. First, let's take a look at the resulting code and then we'll talk through what changed and how each item was addressed.

First, the HTML:

<a

href="javascript:void(0)"

class="menu-trigger"

data-toggle-class='{ "#my-menu": "active" }'

>

Menu

</a>

<div id="my-menu" class="menu">

<!-- Menu Content -->

</div>

<!-- ... -->

<a

href="javascript:void(0)"

class="modal-trigger"

data-toggle-class='{ "#my-modal": "active" }'

>

Modal

</a>

<div id="my-modal" class="modal">

<!-- Modal Content -->

</div>And the JavaScript:

$(document).ready(function () {

// Iterate over all [data-toggle-class] elements.

$("[data-toggle-class]").click(function (event) {

// If it happens to be an anchor with an href, prevent the browser from

// following the link.

event.preventDefault();

// Iterate over the data-toggle-class object and toggle the given class for

// each element.

$.each($(this).data("toggle-class"), function (selector, klass) {

// For example, for the menu, selector would be "#my-menu" and klass would

// be "active".

$(selector).toggleClass(klass);

});

});

// ...

});Okay, so how were each of the six issues addressed?

It's DRY. Previously there were two separate JS event handlers looking for a specific element. Now there's only one targeting all

[data-toggle-class]elements.The targets are set explicitly. Data attributes can optionally be passed a value. And that value can be a JavaScript object. The new JS event handler generically looks for

[data-toggle-class]elements to be clicked upon. When the click action occurs, it looks at the object passed to that element'sdata-toggle-classattribute.In the menu example, the object is

{ "#my-menu": "active" }. So, we iterate over the object and take the keys as the target selectors and the values as the class to toggle. When "Menu" is clicked upon, the$('#my-menu')element toggles anactiveclass. In other words, this would be no different than writing$('#my-menu').toggleClass('active'). But with this new approach, the JavaScript doesn't have to know anything about the elements its working with (other than which element to target for the event listener).Note that this approach also supports one trigger toggling a class on multiple targets. That wasn't necessary. You could just as easily decide you only want to support one and are going to not use an object, but a comma-separated list. Or maybe you'd use two data attributes. The point here is not about the specific example but the idea that the JS code should have minimal knowledge about the markup it's working with.

Scope is not shared. Because I'm using a generic selector (

[data-toggle-class]), everything within the click event handler callback is specific to the element that was clicked. Therefore, when processing a click on the "Menu" element, we know nothing about the modal element. And that's good because we don't need to know anything about that element at that time.Distance between definitions and actions are minimized. Here everything is nice and close together so we don't have to go hunting for any variable declarations.

CSS is determining the visibility. Notice there is no show or hide anywhere in the JS. It's only toggling a class -- an

activeclass, to be specific. The idea here is that the CSS would use theactiveclass on these elements to show or hide them appropriately. You could use any class here and write the styles for it however you'd like. The important part is that CSS is handling visibility and JS is only controlling whether or not the object has a given class.HTML classes no longer determine functionality. That's because the JS is targeting data attributes rather than classes. And to take it one step further, when defining the

data-toggle-classattributes, notice that they are targeting an ID and not a class. This is so we look at a specific element. This is better than targeting a class because IDs are meant to be unique to a page, while classes could occur multiple times. This is good practive even when you know a class only occurs once on a page.

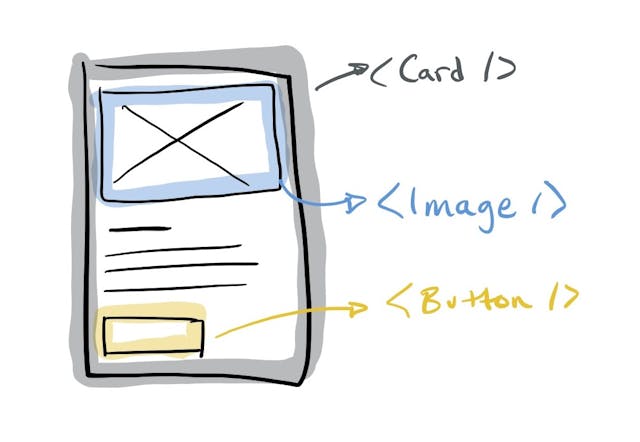

We Have a Component!

Now, arguably, the JavaScript is built with a component-based design in mind. Previously the JS was targeting two specific elements. The new approach didn't care about what those elements were, only what they did. The JS is purely functional by focusing on the behavior of the elements.

Thus, we have a toggle-class component!

One Step Further

But, the JS code is still stuck in this potentially long main file. In a solid component-based architecture, you'd have separate files for each of your JS components. So the file we ended up with may be called something like toggle-class.js and would only contain the code necessary to make the elements toggling classes on other elements work.

That being said, you don't want to load a bunch of small JS files. Instead, you'd want some way to combine them all into a single manifested file. So, ultimately you end up with what we have now, but you don't have to work that way.

This next step requires a build pipeline to combine JS files, and we're not going to cover that here.

One More Step

And if you wanted to go even further, you might consider how you could make this object-oriented by working with JavaScript classes. This is a really simple example, but as your JS becomes more complex, classes can really help separate and clean up code that was otherwise stringy and complex.

However, this approach likely involves transpiling your code (with something like Babel) to earlier version of JS so you can support all the necessary browsers for your project. And we're not going to cover that here.

So that's it. This was a quick look at a way to take messy JS code from a stringy, segmented mess, and turn it into something clean and extendible without too much extra effort.

This moved fast and didn't cover all the odds and ends. So if you want to talk more about it, please feel free to bug me.