Building a Static API with Middleman

Learn to build a static API using the Middleman static site generator.

This article is part of a series of tutorials on building a static API. You can view the full list of available static API tutorials in the introductory article, which also provides some background on the examples we're using here.

If you'd like additional information on what a static API is, check out WTF is a Static API?

This tutorial will walk through building a static API using Middleman. Middleman is a static site generator written in Ruby. It pulls a handful of conventions from Ruby on Rails, which is what first attracted me to it.

Oh, and hey! This tutorial also marks one of the first with an accompanying video! If that's more of your style of learning, watch the video below instead:

The written tutorial follows. But if you're just looking for the code reference, you can find that here.

Step 1: Getting Started

I'm going to assume that if you're here to learn about building a static API with Middleman, you already have some experience with the framework. If not, I encourage you to check out its documentation on installing and starting a new project.

I called my project middleman-static-api, and I used the default starter template, which means my init command looked like this:

$ middleman init middleman-static-api

That command cloned the default starter template and installed the bundle (ruby gems). So now we're ready to go, all we have to do is change into that directory:

$ cd middleman-static-api

Step 2: Add Data Files

We're going to use the data examples from the intro article. Middleman's convention is to put data files in a data directory. While it's not the only option, using the data directory means they will get picked up automatically and be available in your front-end templates.

Grouping the files within a subdirectory in the data directory means they will be available through a variable matching that name. For example, if we put all our data files in data/earworms/... they would all be available via data.earworms in the config.rb file and in our templates (more on this later).

Another Middleman convention is to use YAML files, although JSON files will also work.

So, we're going to create one file for each earworm (again, if you care to, check out the intro on background to our scenario). We could put all these earworms in a single file at data/earworms.yml, but eventually it'll become difficult to manage. I find it easier to use separate files for individual pieces of content.

Here are our three files:

data/earworms/2020-03-29.yml

---

id: 1

date: 2020-03-29

title: Perfect Illusion

artist: Lady Gaga

spotify_url: https://open.spotify.com/track/56ZrTFkANjeAMiS14njg4E?si=oaaJCMbiTw2NqYK-L7CSEQdata/earworms/2020-03-30.yml

---

id: 2

date: 2020-03-30

title: Into the Unknown

artist: Idina Menzel

spotify_url: https://open.spotify.com/track/3Z0oQ8r78OUaHvGPiDBR3W?si=__mISyOgTCy0nzyoumBiUgdata/earworms/2020-03-31.yml

---

id: 3

date: 2020-03-31

title: Wait for It

artist: Leslie Odom Jr.

spotify_url: https://open.spotify.com/track/7EqpEBPOohgk7NnKvBGFWo?si=eceqQWGATkO1HJ7n-gKOEQStep 3: Create Index File

We now have our data, but we haven't surfaced it anywhere on the front-end. We're going to do so through our index file, or the file that will list all the data we've created (i.e. all the earworms).

While we could simply make this the home page of the site, remember that we're building an API. It's a good practice to make URLs declarative and semantic. Therefore, instead of having the actual index path spit out all the data, I'd prefer to nest earworms under /earworms. That way we are setting ourselves up to expand to other types of data in the future without having to rewrite code for the sources already consuming the API.

Middleman pulls much inspiration from Ruby on Rails, and one of those is the way in which it handles templating. Middleman prefers ERB templates, but supports a few others out of the box, with options to expand from there.

The file-naming is a little weird when working with Middleman templates because you will often see multiple extensions on a file. They are processed from right-to-left. That means that if I have a file named hello.json.erb, Middleman is going to first process the file as a .erb file, and then as a .json file.

That's the approach we're going to take here, too, as we want our file to ultimately be a .json file. And while we could use a tool like jbuilder, I'm going to show you how simple it is to write these JSON files by hand using Ruby libraries.

But first, let's start by creating our file at source/earworms.json.erb and making sure we're setup correctly. Because this is JSON, we'll just include an empty object to start:

source/earworms.json.erb

{}Preview Time!

Now is the time to make sure you have everything installed as expected and can get to this page. Start your server:

$ bundle exec middleman

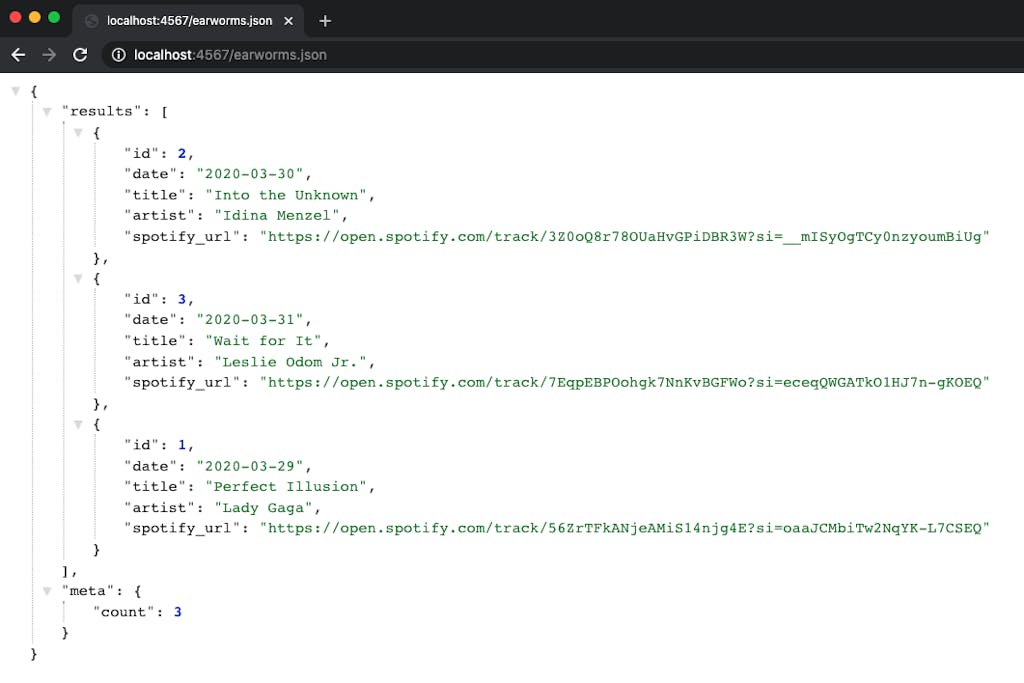

And then visit localhost:4567/earworms.json to see the result. You should see an empty object.

Add Meta Data

Following the direction of the intro article, let's next add meta to our object. We learned in the intro that it's a good practice to put our results in a results object so that we have more flexibility to change the structure of the response down the road.

For now, all we want to do is return the count, or the number of earworms that we have in the collection. To do that, we can use Ruby's JSON module. The generate method will help us convert a ruby hash or array into valid JSON, and we could even make it pretty (we're not going to worry about that, though).

source/earworms.json.erb

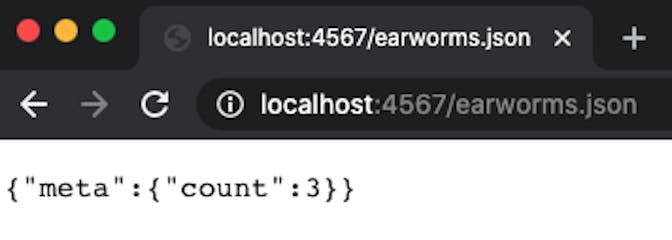

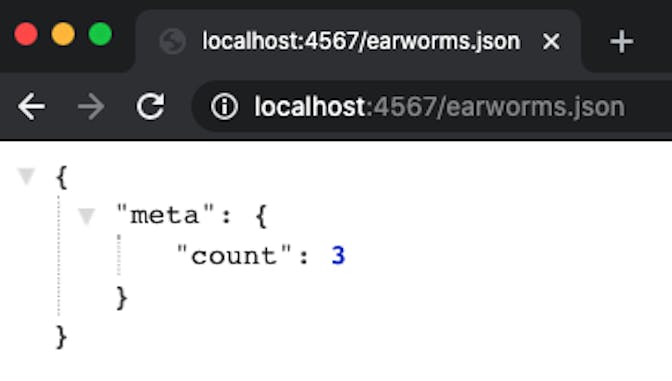

<%= JSON.generate({ meta: { count: data.earworms.size } }) %>Now, refreshing the page, you should see the count of 3 nested within a meta object.

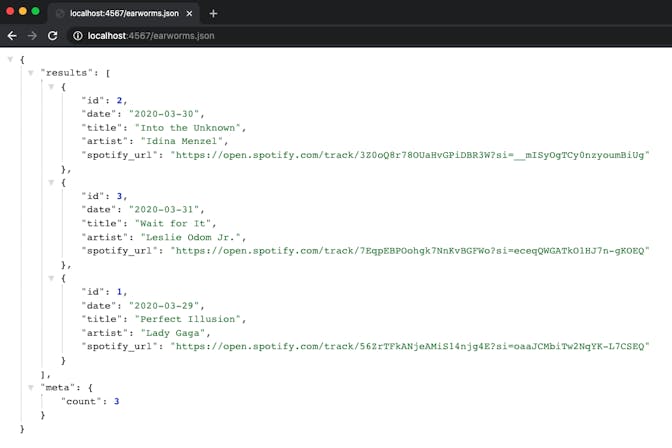

I like using a Chrome extension to format JSON for me. It's called JSON Formatter. It cleans up the output to look like this:

Add the Earworms Data

Now that we've gotten our feet wet, let's add the earworms data within a results array. Here's the code:

<%= JSON.generate(

results: data.earworms.values,

meta: {

count: data.earworms.size

}

) %>Refresh the browser and you should see all the data.

Let's go back to how we got all that data from data.earworms.values.

First, we know that data is a collection of everything within the data directory. And our data is available via data.earworms because we've nested our data files under an earworms directory.

But if we were to look at what class data.earworms is, we'd get Middleman::Util::EnhancedHash. It's a custom utility coming from Middleman. It's kind of like an array and kind of like a hash, where the first element (or the key) is the name of the file without the extension, and the second is the parsed content of the file.

And we have methods we can run on hashes, like keys and values. So if we tried data.earworms.keys we'd get:

["2020-03-30", "2020-03-31", "2020-03-29"]Step 4: Add Individual Files

As our last step here, let's create individual files so that if we want to get data just for a single earworm, we can do so by going to /earworms/[id].json where [id] is the id attribute coming from the data files we've created.

In this case we don't want to have to manually create a template for each data file — that defeats the purpose of having data files. Instead we can use the config.rb file to create dynamic pages using the proxy method. That code looks like this:

config.rb

# ...

data.earworms.each do |date, worm|

proxy(

"/earworms/#{worm.id}.json",

"/earworms/template.json",

locals: { worm: worm },

ignore: true

)

endLet's talk about what's going on in a few places here.

If you're used to Ruby code, data.earworms.each do |date, worm| may look a little weird because it's passing two objects to the block. As I mentioned above, this is because the first value is the name of the file without the extension. (I called it date because in our case it represents a date.) And the second object (worm) is the parsed data from the file.

With proxy, the first argument is the path to where the page should live and the second is the template. So we're saying use a template at source/earworms/template.json and proxy that to a page at /earworms/[id].json. (Notice that you don't need the .erb at the end of the template filename.

locals is an object which passes data into the template. In this case, we're passing worm into the template, which means we can use the variable worm in our ERB code, as you'll see below.

And finally, ignore: true tells Middleman to not process the template file as a page on the front-end of the site.

The template itself is super simple.

source/earworms/template.json.erb

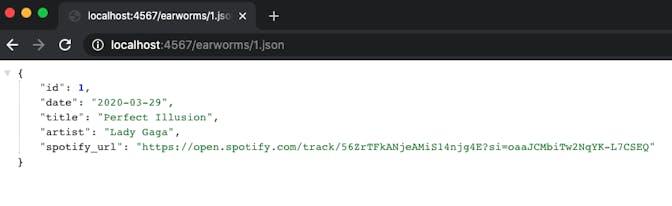

<%= JSON.generate(worm) %>Restart your server and then try it out in the browser at localhost:4567/earworms/1.json and you should see the data for Perfect Illusion, which was the data file with the id value of 1.

You can try the same thing with 2.json and 3.json, but notice that any others should throw a 404 error.

Cleaning Up

And that's it! Now you have an API. There's a route that lists all your earworms and individual routes for each earworm. Now you can deploy that and use it wherever you'd like!

That said, some tasks you may want to consider before taking something like this into production:

- Ensure you have proper header rules so that you're protecting against CORS and also delivering these files with the appropriate MIME type. If using a service like Netlify, most of this will be done for you.

- Remove the default home page because this site is meant to be an API. You may even consider redirecting the home page to the

/earworms.jsonpath temporarily. - You can also consider redirecting all requests that don't end in

.jsonto append the.jsonto them. Another option is to remove.jsonfrom your file extensions, while making sure the MIME type remains correct. - And you may even want to control the order of the earworms on the index page.

References: