A Brief Introduction to Inlining Critical CSS

Although more applicable to traditionally-built sites, inlining critical CSS can be a quick and easy performance boost for your site, especially as it grows.

More traditional static sites (those directly loading one or more global stylesheets) often see their CSS files become bloated over time. And that makes sense — as the site grows, it requires more custom behavior and styles.

This bloat can lead to degraded page speed performance and longer load times for your users.

Why CSS Bloat Matters

When a page loads, CSS files are typically loaded synchronously, also referred to as render-blocking. This is because you want your browser to know about the styles before presenting content to the user. Otherwise, you run the risk of content first rendering without style, which is not a good experience.

The larger a CSS file gets, the longer it takes to download, which ultimately means more time before your users see anything on the page.

The Inherent Problem with Global Stylesheets

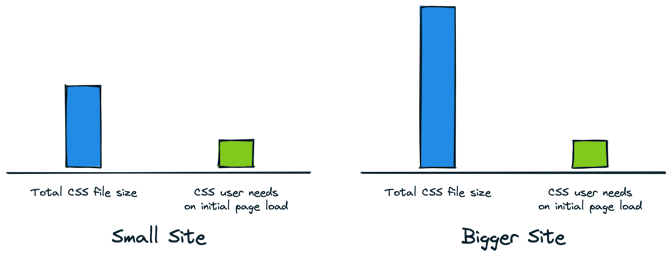

While it makes sense that a global stylesheet would grow over time, it results in a user of a single page downloading the supporting styles for a growing website, when all they really need is the CSS code that supports the content they are viewing at that time.

Inlining Critical CSS

It’s for this reason that the pattern of _inlining critical CSS _emerged to solve these problems.

Critical CSS consists of the styles needed to present the content above the fold (or within the viewport) when the page is first loaded.

Inlining is to write those styles inline programmatically. Thus, when the page is first loaded, the only styles the user’s machine had to download were those that affect the content they are viewing. Meanwhile, the remaining CSS loading is deferred and loaded asynchronously, thus not blocking the rendering of the page. Theoretically, this means that by the time they begin scrolling, the rest of the styles are in place.

Tools for Critical CSS

The beauty of this approach is that there are tools that can handle doing this work programmatically for you. The one I use the most is the Node.js-based critical package. This provides numerous options for reading HTML and CSS files, before adjusting the HTML code to optimize the performance of the page.

There are likely additional tools that support the server-side language you’re using for your site.

Alternative Approaches

Modern frameworks tend to be better at optimizing CSS performance out of the box, although there’s always a risk of CSS slowing down your site. It’s for that reason that tools like Tailwind have become so popular, as they provide a means to build custom user interfaces with minimal addition to the stylesheets downloaded by users.

Whatever your approach, it’s always worth looking into requiring a user’s browser to do the minimal amount of work necessary to consume your content the way you’ve intended. Everything beyond that is an unnecessary lowering of your site’s performance.