Abstract hard-coded values in your code

When JS frameworks don’t bring low-level structure recommendations on constants, configuration, and content, you’ll benefit from establishing your own conventions.

The natural move for a developer is to define values where they are used.

Say you have a utility function that makes a call to an API to return a list of users. That might look something like this:

export async function getAllUsers() {

const response = await fetch("https://api.myapp.com/users");

const data = await response.json();

return data;

}The typical path to abstraction

Most apps need more than this single function. Soon, you'll also want a list of teams, let's say.

export async function getAllUsers() {

const response = await fetch("https://api.myapp.com/users");

const data = await response.json();

return data;

}

export async function getAllTeams() {

const response = await fetch("https://api.myapp.com/teams");

const data = await response.json();

return data;

}Well, now you've duplicated code, and we were taught not to do that. It must go! So we end up with something like this:

async function apiGet(urlPath: string) {

const response = await fetch("https://api.myapp.com/" + urlPath);

const data = await response.json();

return data;

}

export async function getAllUsers() {

const users = await apiGet("/users");

// do something with users ...

return users;

}

export async function getAllTeams() {

const teams = await apiGet("/teams");

// do something with teams ...

return teams;

}Then, you set up a staging environment so you're not using production data locally, which means you need to swap out the base API URL. You also need to update user data. And so on. The layers of abstraction continue.

const BASE_API_URL = process.env.BASE_API_URL;

async function apiGet(urlPath: string) {

const response = await fetch(BASE_API_URL + urlPath);

const data = await response.json();

return data;

}

async function apiPost<T>(urlPath: string, data: T) {

const response = await fetch(BASE_API_URL + urlPath, {

method: "POST",

body: JSON.stringify(data),

});

return response.json();

}

export async function getAllUsers() {

const users = await apiGet("/users");

// ...

}

export async function getAllTeams() {

const teams = await apiGet("/teams");

// ...

}

export async function createUser(user: User) {

const newUser = await apiPost("/users", user);

return newUser;

}And at this point, most developers think, I need a better system for managing this. Complexity requires systems to be maintainable.

Using global constants

In scenarios like this, I introduce global constants into the codebase — a single source of truth for storing and managing hard-coded values (that may change). I'd first add a new constants file.

src/constants.ts

export const BASE_API_URL = process.env.BASE_API_URL || "https://api.myapp.com";

export const ROUTES = {

users: "/users",

teams: "/teams",

};And then import those constants into the application code.

src/utils/api.ts

import { BASE_API_URL, ROUTES } from "../constants";

async function apiGet(urlPath: string) {

const response = await fetch(BASE_API_URL + urlPath);

const data = await response.json();

return data;

}

async function apiPost<T>(urlPath: string, data: T) {

const response = await fetch(BASE_API_URL + urlPath, {

method: "POST",

body: JSON.stringify(data),

});

return response.json();

}

export async function getAllUsers() {

const users = await apiGet(ROUTES.users);

// ...

}

export async function getAllTeams() {

const teams = await apiGet(ROUTES.teams);

// ...

}

export async function createUser(user: User) {

const newUser = await apiPost(ROUTES.users, user);

return newUser;

}Identifying abstraction triggers

YAGNI is an excellent practice. It keeps developers focused on the task at hand and prevents us from over-engineering solutions that we probably won't need.

When you're building out prototypes with modern JavaScript tooling, this is a great paradigm to follow. Work within the framework, use only what you need, test your theories, and evolve.

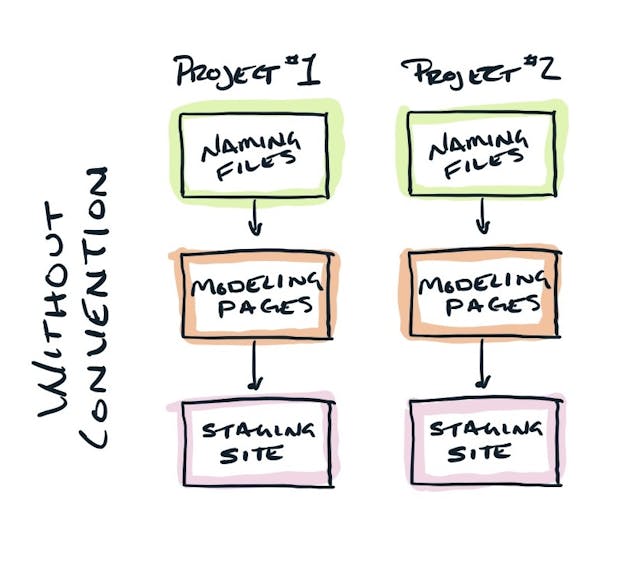

The challenge is that if you're going to build a production application, most modern frameworks don't establish conventions to keep you focused. Low-level code decisions are left to you. I've written about the benefits of having a convention many times (see here, here, and here for three examples).

This is a convention that is necessary on almost any production application. For that reason, the trigger I use to determine whether to establish the practice at the outset of the project is based purely on the project's expectations. If I'm testing something to share and discard, or something I expect to lead to another project, then it's not worth the effort. But if I'm green-fielding an application that I plan to take into production and support, I start here, right from the beginning of the project.

Variations on constant

This practice can be applied to similar concepts, and it has tangential practices that I adjust based on the project at hand.

Filenaming conventions

Constants are a form of configuration. An application may be complex enough that it makes sense to abstract a whole slew of configuration-like values. For that reason, you may choose to call your file config.ts instead of constants.ts, knowing that it will require more than hard-coded constant values.

Hard-coded content

When it comes to content that is hard-coded in the UI, such as the label of a button in a form, I typically place these files in a src/content.json file (note the JSON file type).

The difference between <button>Update user</submit> and <button></button> may seem trivial at first. But it makes finding your place and being consistent so much easier. When you consolidate all your form content in one place, you can clearly see where the differences are and present a better experience to your users.

Handling values at scale

I typically adhere more to YAGNI principles when architecting the constant files themselves. I usually start with a single set of files (constants.ts, config.ts, content.json), and introduce semantic groups only as the application grows in complexity. For example: config/routes.ts and config/api.ts.

TypeScript import paths

If you're using TypeScript (as I've shown in the examples here), you can take advantage of import paths. This allows me to use the same import regardless of where the consuming file is in the application. In my tsconfig.json file, I can add this:

tsconfig.json

{

"compilerOptions": {

"baseUrl": ".",

"paths": {

"@constants": ["src/constants.ts"],

// ...

}

}

}And then in the consuming file, you always import from @constants.

import { BASE_API_URL, ROUTES } from "@constants";

// ...Find your pattern

This is simply what I've been doing lately. Use it and adjust it. Find a pattern that works for you. And I'd love to hear about it, as I suspect my patterns will change as I evolve my approach to building applications over time.